Shouting louder may allow you to be heard, but you still might not be understood! The phonetic alphabet is all about pronunciation: how writing sounds. To speak a language intelligibly, it is important to stress the correct syllables in a word and to enunciate correctly. This is where the phonetic alphabet comes in, which you can see in the image further down in this post.

The International Phonetic Alphabet is widely used in linguistics, language learning, speech pathology, and other fields related to the study and analysis of speech sounds. It serves as a valuable tool for accurately representing and transcribing the sounds of human languages from around the world. For language learners, it is an invaluable resource that tells them exactly how to pronounce a word that may otherwise not be self-evident, as is especially the case with the English language, whose word spellings are notoriously renowned for not reflecting their pronunciation!

The phonetic alphabet

The phonetic alphabet is a type of spelling system that uses letters and symbols to represent the individual sounds of the language. These letters and symbols are organised into a chart that enables one to understand how words should be pronounced by looking at their phonetic spelling rather than their standard spelling.

The history of the phonetic alphabet dates back to ancient times, with various attempts made throughout history to develop systems for representing the sounds of human speech. However, the modern concept of a phonetic alphabet, as we know it today, can be traced back to 1867 when several scholars began developing phonetic alphabets to accurately represent the sounds of human speech. Notable contributors include Alexander Melville Bell and his son Alexander Graham Bell who developed the ‘Visible Speech’ system, which attempted to represent the positions of the speech organs when articulating sounds. Then, in 1886, the International Phonetic Association was founded with the goal of creating a standardised phonetic alphabet. The IPA sought to establish a universal system for transcribing sounds across different languages.

Over the years, the IPA has evolved and expanded, incorporating contributions from various linguists and phoneticians to accommodate a wider range of sounds found in different languages, and modern IPA, known as ‘IPA 2005’, consists of a comprehensive set of symbols that include consonants, vowels, diacritics for additional phonetic features, and suprasegmental features such as stress and intonation. In 2020, the International Phonetic Association further revised the alphabet.

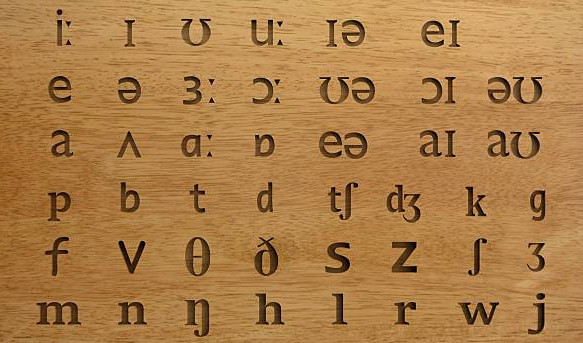

The chart below is a representation of the standard international phonetic alphabet, which is a somewhat deceptive name because, although it was designed to represent all the sounds of human speech and is not limited to English phonetics, it does not represent all the sounds of every one of the 6,500 languages in the world. There are many complex languages in Africa and Australasia that use systems of clicks and other sounds. In addition, the sign languages of the world, for the deaf or hearing impaired, cannot be represented because sign is not a spoken language.

The symbols and letters in the chart below are called ‘phonemes’ and these phonetic spellings are shown in good dictionaries around the world, such as The Cambridge English Dictionary, which shows both UK and US pronunciations for its words.

The phonemic chart

The chart above comprises 44 phonemes. There are 20 vowel phonemes, which are divided into 8 diphthongs (two vowel sounds sounded in close succession) and 12 monophthongs (a single vowel sound), and a further 24 consonant phonemes.

Of course, speakers of English all over the world have dialects and not all dialects use each of the 44 sounds in the above chart. However, whether you are Jamaican, South African or Irish, you will still use a good 40 of these sounds in your speech.

Received pronunciation

There are a great many English accents around the globe and within the United Kingdom alone, so the majority of phonetic representations of spoken British English are actually representative of one of many accents: received pronunciation (unless otherwise specified). For more on the different standard Englishes around the globe, please visit this post.

Great Britain and Ireland were countries that were inhabited by Celtic tribes with many languages and dialects even before the Roman takeover in the first century, the invasions of Germanic tribes from the fifth century, the subsequent invasions of Vikings and Danes from the eighth century onwards, and the influence of the French-Norman invasion that followed and lasted several hundred years. By the time the Crown and the language of politics, church and education, as well as the common tongue, had been decided upon to become exclusively English, there was no standard form of English at all. It was not until the mid-eighteenth century that Samuel Johnson established a regular form of spelling and published the first real English dictionary. This standardisation of the written language led to a desire for a standard in the spoken language too, and this standard of ideal-sounding British speech has been termed ‘Received Pronunciation’. Regardless of the regional dialects of the people, educated people were expected to speak with received pronunciation, and those that came from abroad desiring to learn English were taught received pronunciation. Received pronunciation originated in the English capital, where the ruling class, royalty and noblemen, as well as clergy and the men of the finance world were largely based. Today, received pronunciation is still somewhat reflective of the class and education of its speakers, and people who wish to speak ‘correct English’ often view RP as an accent to be aspired to.

Thus, the beauty of the phonetic alphabet is that it can show not only how a word should be pronounced in one region, but how it factually is pronounced elsewhere. The phonetic alphabet can be used to represent different accents as well as different languages:

Spelling: Cup

- A speaker with received pronunciation (generally the southeast of England) phonetic spelling = cʌp

- A person from Yorkshire (an area in the northeast of England) phonetic spelling = cʊp

So the letter ‘u’ is symbolised by a phoneme that represents the pronunciation of that vowel sound in that region.

The Cambridge dictionary habitually represents words with phonetic spellings for both the UK and the US, but its UK phonetic spelling represents RP and its US phonetic spellings represent General American pronunciation:

Spelling: Not

- UK received pronunciation phonetic spelling = nɒt

- US General American pronunciation phonetic spelling = nα:t

Once again, the central letter, this time ‘o’, is symbolised by a phoneme /ɒ/ or /α:/ that represents the pronunciation of that vowel sound in that country. The English RP ‘o’ is short in ‘not’; the General American ‘o’ has a longer sound in the word ‘not’.

Vowels

Here are some examples for each vowel phoneme. I have listed a variety of spellings so that the reader will see how one pronunciation can be represented by numerous spellings. Have a close look at the list of letters and symbols below that represent all the existing vowel sounds. You will notice that some of the letters and symbols represent multiple spellings as well as sounds that are not always reflected by their spelling. Observe, too, that some identically spelt words can occur with multiple pronunciations giving them different meanings.

Where a colon follows the symbol, the vowel sound is one sound but long; where no colon follows the symbol the sound is short. Where two symbols are shown close together, there are two sounds within the single phoneme; it starts on one sound and changes as it is uttered.

In polysyllabic words, the relevant vowel symbol has been underlined:

- ɪ = pit, fit, lit, split, give, till, sin,

- i: = key, she, glee, free, leigh

- e = pet, forget, arrest, test, better

- α: = car, far, are, garlic, marmalade

- æ = pat, cat, hat, mat, fat, attract

- ᴐ: = core, war, sure, floor, water, wall, pork, fork

- ʌ = but, cut, shut, nut

- u: = chew, shoe, flew, do, who, loo, glue, rude, route

- ɒ = pot, got, not, what, hot

- з: = incur, slur, fur, girl, learn, sir, work

- ʊ = put, foot, nook, could, hook

- ə = about, upper, hesitant, today, classical, helplessness, minimum, invalid, dependent, velvet, (schwa)*

- eɪ = bay, okay, neighbour, weigh

- əʊ = go, bow, slow, show, grow, flow

- aɪ = buy, cry, sly, shy, arrive, die, kite, light

- aʊ = cow, bow, now, house, mouse

- ᴐɪ = boy, deploy, annoy, soil, toy

- ɪə = peer, dear, near, tear

- eə = pear, share, fair, tear, nightmare, there

- ʊə = pure, mature, assure, during, security

* This symbol /ə/ is known in English as the ‘schwa’ sound. Especially in UK English, many syllables are pronounced this way, regardless of what vowel is used to spell them, because they fall on a vowel that is unstressed when spoken.

Have a go at spelling each of the above words phonetically, and then have a look in The Cambridge English Dictionary and see how you did. Compare their phonetic spellings with their standard spellings.

Consonants

Here are some examples for each consonant phoneme. I have listed a variety of spellings so that the reader will see how one pronunciation can be represented by numerous spellings. Have a close look at the list of letters and symbols below that represent all the existing consonant sounds. You will notice that some of the symbols, like /j/ and /k/, represent sounds that are not always reflected by their standard letter spelling:

- b = bee, boy, bump, below, big, by, brown

- d = dog, door, down, do, develop, drive

- f = fly, for, first, figure, flow, fry, find, fetch

- g = gap, goat, ground, guilt, go, get, glitch

- h = help, how, high, hope, hat, hog, hug

- j = yet, yacht, yellow, yawn, you, yesterday

- k = kite, cat, can, collect, kitten, crew, could

- l = let, leave, low, live, lord, litter, level, last

- m = mother, map, mat, make, mould, move

- n = now, never, not, night, neither, nor, nice

- p = perfect, pet, please, port, post, pit, pot

- r = red, rest, rope, race, right, rug, really

- s = stop, slow, sit, sat, send, super, sold

- t = take, top, trip, trend, time, tickle, test

- v = voice, vet, vest, van, vicar, vulture

- w = wear, what, well, west, wing, wolf, wonder

- z = zip, zest, zone, zoom, Zulu, zebra

- Ӡ = measure, invasion, division, occasion, television

- ʤ = jet, jump, joke, January, gin, ginger, general

- ʧ = chin, check, church, chips, China, choose

- ʃ = ship, shore, shine, shoe, show, shirt

- θ = thing, think, thought, through, three, thank

- ð = this, that, the, those, these, they, them

- ŋ = hang, sing, thing, ring, bring, jingle, loving

Conclusion

The examples given above all reflect English Received Pronunciation and will also look different if they are to reflect an American or Australian accent, or for that matter any of the numerous accents around the United Kingdom and the globe.

Have a look in a dictionary that lists phonetic spellings beside standardised spellings and experiment with pronouncing the words according to the given phonetic spelling.

If you have any questions or comments, or fun examples, please enter them below.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Börjars, Kersti, and others. Introducing English Grammar, 2nd edn (Routledge, 2010)

Crystal, David. Spell it Out: The Singular Story of English Spelling (Profile Books, 2013)

Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, 3rd edn (Cambridge University Press, 2019)

Hickey, Raymond. Standards of English: Codified Varieties Around the World (Cambridge University Press, 2015)

Huddleston, Rodney, and others. The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (Cambridge University Press, 2002)

Plag, Ingo, and others. Introduction to English Linguistics (Mouton de Gruyter, 2007)

Quirk, Randolph, and others. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language, reprint edn (Pearson, 2011)

Roach, Peter. English Phonetics and Phonology: A Practical Course, 4th edn (Cambridge University Press, 2009)

Thorne, Sarah. Advanced English Language, 2nd edn (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008)

Yule, George. The Study of Language, 4th edn (Cambridge University Press, 2010)

New Hart’s Rules: The Handbook of Style for Writers and Editors (Oxford University Press, 2005)

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/

https://www.oed.com/

https://www.merriam-webster.com/

I agree that the name of the standard international phonetic alphabet is a deception. Although they may be correct when checked with the British. Not all of them will align with other accents. As you rightly identified, there are a lot of complex languages in Africa. From Zulu and Swati to Yoruba and Hausa in Nigeria, they are all unique languages with their accents and alphabets.

Hi Parameter. Thank you so much for your comment. Yes indeed, and there are also many hundreds of languages in Indonesia and Australia and elsewhere! It is high time the IPA was appropriately renamed.